How the Anglosphere's Planning Department is YIMBYism’s Main Obstacle

Montreal doesn't have these problems! Francophones beat us on this one.

The moment I understood the true nature of urban planning in Ontario came during Bonnie Crombie's campaign for leader of the Ontario Liberal Party. For years, the OLP had lacked any coherent housing policy. Then, suddenly, during the leadership race, every candidate emerged with detailed plans to build more homes. Crombie, the former mayor of Mississauga, had spent her political career as a textbook NIMBY—opposing density, fighting development, championing the suburban status quo that had defined her city.

But something remarkable happened during her campaign. YIMBY advocates within the party and on her team helped her see differently and more clearly. She abandoned her old positions and embraced ambitious housing targets, zoning reform, and streamlined approvals. The transformation was complete and genuine. Yet it raised an uncomfortable question: where had those "old ideas" come from in the first place?

The answer was as obvious as it was revealing. Bonnie Crombie had just wanted to be mayor, but it was Mississauga's planning department that taught her urban planning. The same pattern repeats across the country: politicians defer to the supposed expertise of their planning staff, absorbing what they believe to be institutional wisdom. In reality, they're inheriting something far different—the crystallized trauma of decades spent trying to appease the unappeasable.

To understand how we arrived at this dysfunction, we need to recognize something unique about the Anglosphere's approach to development. Unlike most of the world, where zoning rules determine what can be built, countries like Canada, the United States, Australia, and the United Kingdom subject virtually every new development to public consultation. Community meetings become forums where the loudest voices—invariably those with the most time and the strongest opposition—shape policy.

The United Kingdom represents the extreme case: famously lacking comprehensive zoning laws, it relies instead on plot-by-plot community input before anything gets approved. Every proposed development, from a single home to a major project, must navigate a gauntlet of public hearings where neighbors can voice their concerns, complaints, and outright hostility.

This system creates what planners experience as an endless parade of opposition. NIMBYs show up reliably to oppose everything: daycares, transit, affordable housing, market-rate housing, bike lanes, parks, libraries. They are implacable in their opposition and unlimited in their creativity when inventing reasons why nothing should ever be built anywhere. Over time, planning departments develop elaborate guidelines designed to address these complaints—shadow studies to measure how new buildings might darken neighboring properties, setback requirements to preserve "neighborhood character," stepback rules to reduce visual impact, floor area ratio limits to control density.

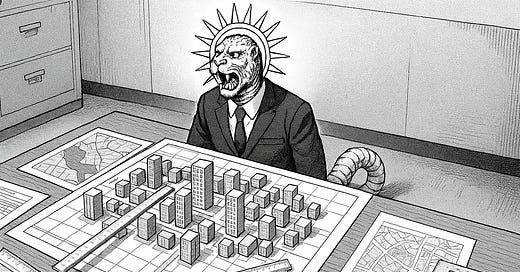

Planning departments become what I call traumatized viziers—institutional survivors encoding decades of public meetings into increasingly complex regulations. They aren't evil or incompetent. They're responding rationally to their environment, developing defensive strategies to minimize conflict. But the result is a body of "institutional wisdom" that is actually the institutional trauma of dealing with unreasonable people, codified into rules that don't solve the underlying problems.

The most insidious aspect of this process is how it teaches politicians. Municipal leaders, many of whom lack deep knowledge about urban planning, naturally defer to their professional staff. They absorb this supposed expertise without questioning its origins. Politicians come and go every four years, but the planning department's institutional memory persists, passing its accumulated neuroses from one administration to the next.

This system creates a fundamental asymmetry that explains why housing advocates have everything stacked against them. NIMBYs have discovered, perhaps accidentally, the optimal strategy for influencing land use policy. Their goal—total opposition to change—is beautifully simple. They need no technical expertise, no understanding of zoning bylaws, no familiarity with planning theory. They simply say no, loudly and repeatedly, until the system bends to accommodate them.

YIMBYs face a far more complex challenge. They want more housing. But unlike NIMBYs, whose brazenly unreasonable demands the system has learned to accommodate, YIMBYs often get trapped trying to engage constructively with technical frameworks designed around obstruction. The planning process forces advocates into technical discussions about floor area ratios, angular planes, and heritage character—debates conducted in specialized language where planners hold every advantage.

Consider the semantic cargo embedded in common planning concepts. Shadow studies sound objective and scientific, but they encode an assumption that any shadow cast by a new building represents harm to be minimized. Setback requirements ostensibly preserve neighborhood character, but they guarantee that new buildings will be smaller and house fewer people. Floor area ratio limits appear to balance competing interests, but they systematically bias outcomes toward lower density.

These concepts aren't neutral technical tools—they're weapons forged in the fires of countless community meetings where NIMBYs demanded that everything be smaller, shorter, and further apart. Engaging with them on their own terms means accepting premises designed to favor the status quo.

When housing advocates learn planning jargon and attempt to engage the system in good faith, they fall into what philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein called a language game. They begin fact-checking shadow studies, debating the merits of different setback requirements, and proposing modifications to floor area ratio calculations. This feels like productive engagement, but it's actually a trap.

You will never win a language game that was stacked against you. The aim of these technical discussions isn't to reach optimal outcomes—it's to signal knowledge and mastery of the planning domain. No matter how much advocates study, they're still outsiders challenging people whose professional identity depends on defending institutional expertise. Who are you, a lowly random civilian, to critique concepts developed by credentialed professionals with years of experience?

The planning staff sitting across from you at public meetings possess an abundance of institutional knowledge and professional designation. They've attended conferences, authored reports, and participated in countless development reviews. Whatever you say will likely bounce off their accumulated expertise and defensive instincts. You're playing their game on their field with their rules.

Meanwhile, there's no point in playing a game where you hold zero power. Planners have home field advantage in technical discussions, but citizens possess something far more potent: constitutional authority. The democratic system grants you, as a voter, the power to set terms of engagement that bypass technical complexity entirely.

This is precisely the game that NIMBYs keep playing and winning. They don't debate angular plane calculations or heritage character assessments. They express emotions, demand specific outcomes, and threaten political consequences if those outcomes aren't delivered. When planners respond with technical objections—citing guidelines, referencing best practices, invoking institutional wisdom—NIMBYs hold the ultimate trump card: they don't care.

The path forward requires abandoning the fantasy that you need to become a planning expert to advocate effectively. Your aim is to win, not to receive an urban planning degree through osmosis. This means embracing strategic simplicity over technical sophistication.

YIMBYs actually have an advantage that they rarely exploit: their demands are more coherent and less contradictory than NIMBY positions. Where NIMBYs oppose everything for incoherent reasons, housing advocates can offer a clearer program: more homes to create abundant supply and cheaper prices, streamlined regulations that govern land through rules rather than the whims of loud neighbors, and bigger units for everyone whether they're single people or families with children.

These demands cut through technical smokescreens and force binary choices. When planners respond with objections about setbacks, stepbacks, or floor area ratios, advocates can simply note that these regulations need to be fixed to achieve bigger homes and more abundant supply. When they cite institutional wisdom or professional experience, the appropriate response is dismissive: the current system isn't working, so that expertise has proven inadequate.

And it works: being dismissive of regulations like floor plates and shadow studies by simply questioning the wisdom of their guidelines in public meetings. Rather than engaging with their technical frameworks, press them on fundamental contradictions: "Why do shadow studies exist when we are in a housing crisis and they so clearly conflict with the livability of apartment and condo units?" When they spend fifteen or twenty minutes defending shadow studies as essential planning tools to increase your Vitamin D intake—this actually happened—let them make their vapid appeals to professional authority while refusing to confront the question.

You can also ask planning staff questions designed to hold them to higher standards. You know precisely which ones: questions where the answer is something they should know, but their inability to respond reveals fundamental weaknesses in their profession.

The key is remembering that you are conducting a form of "question period" where the planner's due diligence is under scrutiny. Has an economic tradeoff study been conducted on how shadow regulations or floor area ratios impact unit livability and affordability for the building being constructed? The question will upset them because they can't answer it—they usually don't study the economic impacts of their guidelines—but it's valid, and in the absence of comprehensive planning reform, it's one of the clearest pathways available to hold planning staff accountable to higher standards.

The most significant barrier to this approach isn't technical—it's cultural. We've developed a norm that insulates planning staff from direct criticism, with the refrain "don't critique staff, critique politicians" repeated whenever citizens challenge professional recommendations. This sounds reasonable and good-hearted, treating municipal employees as separate from politics and protecting them from unfair attacks.

But this separation is often illusory, and citizens who engage with it as if it were real stunt their own capacity to recognize structural problems. When planning staff are immune from criticism, politicians never learn what's wrong with their recommendations. Municipal leaders are often busy with many responsibilities, taking instruction from staff rather than exercising independent judgment about urban planning issues they rarely understand deeply.

Politicians can't reform what they don't see as wrong. If citizens dutifully direct all criticism toward elected officials while treating planning recommendations as neutral technical advice, the source of dysfunction remains invisible and unchanged. The protection racket continues, with traumatized viziers teaching institutional neuroses to successive generations of politicians.

Breaking this cycle requires abandoning deference to planning expertise and holding the entire system accountable for outcomes. This doesn't mean citizens need to become planning experts—quite the opposite. It means insisting that expert knowledge serve democratic priorities rather than demanding that democratic participation defer to expert preferences.

The broader lesson extends beyond housing policy to any domain where professional expertise has become weaponized against democratic accountability. Citizens should absolutely understand how systems work—knowledge is valuable and ignorance is dangerous. But when it comes to advocacy, technical sophistication often proves counterproductive.

The most effective advocates combine deep understanding with strategic simplicity. They know enough about planning regulations to recognize when they're being manipulated by technical language, but they refuse to get trapped in debates conducted on unfavorable terms. They demand better outcomes and make life difficult for officials who fail to deliver, regardless of whatever professional justifications those officials might offer.

This approach requires a fundamental reorientation away from good faith engagement with bad faith systems. It means treating institutional wisdom with suspicion rather than deference, especially when that wisdom consistently produces outcomes that benefit established interests over broader public welfare.

The housing crisis won't be solved by citizens becoming better amateur planners. It will be solved when citizens become more effective at wielding democratic power against professional classes that have insulated themselves from accountability. The choice is simple: keep playing a rigged game designed to exhaust and frustrate you, or change the rules entirely by refusing to play.

YIMBYs and transit advocates who recognize this dynamic hold the potential to transform not just housing policy, but the broader relationship between expertise and democracy. The question isn't whether you understand floor area ratios—it's whether you're willing to demand better outcomes regardless of what the professionals say. That's a much simpler game, and it's one you can actually win.

I am a planning commissioner and I thank you for wandering into my head and pulling out thoughts that have been swirling around for a decade. One angle I hadn't thought of was the Anglosphere/Francophone divide, and I hope you get into how the latter system works! Like a whole article on it. I would love that.

Excellent read! I'm just wondering where the difference between Québec and ROC stems from. Is it just different rules, or is it more cultural factors?

(As a French immigrant, I’m baffled by the level of engagement for each and every project)